‘Destroyed’: Family Mourns Death in Norman, Oklahoma

'Destroyed': Family Mourns Death; Data Contradicts OHP Pursuit Claims

By Max Bryan, The Norman Transcript //

August 28, 2022

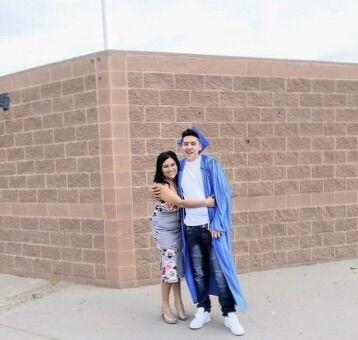

Those close to Ethan Mestes will tell you his face lit up a room — a reflection of his warm, happy personality.

Mestes lived in Pueblo, Colorado, where he remodeled homes. When he wasn’t working, he was with his friends at the motorcycle track.

“He was a good kid,” said Mestes’ uncle, Johnny Alires. “He was a good friend. He was a good nephew.”

Mestes, 22, died Aug. 15 when an Oklahoma Highway Patrol trooper spun out a fleeing Ford Ranger on Interstate 35.

Mestes and Mercedes Martinez, 26, were ejected from the truck. Mestes was pronounced dead at the scene; Martinez was in critical condition after the pursuit.

Questions have been raised for a long time about police pursuits, but at least one expert and one study challenge the decision to pursue in most cases, indicating that when a pursuit is called off most of the time the fleeing vehicles slow down to near the speed limit within two minutes.

The findings contradict claims OHP has given as reason for pursuing and spinning out the truck.

The pursuit

Alires said his nephew had traveled to Oklahoma City to be with his friend, Martinez, whose father and brother had just died. He and Martinez were in the car with Alex Carpenter, the father of Martinez’ children, when the trooper spun out the car.

On the evening of Aug. 15, OHP trooper Nick Mills chased Carpenter, the driver, on Interstate 35 from south Oklahoma City to Norman after Carpenter failed to pull over for an equipment violation.

Mills discovered after he had engaged in the pursuit that the tags on the Ford Ranger were stolen, according to a probable cause affidavit filed Monday in Cleveland County District Court.

Trooper Eric Foster previously said Carpenter veered at the troopers during the pursuit.

Mills was placed on administrative leave immediately after the pursuit for internal investigation.

The affidavit was used to charge Carpenter, 30, also of Pueblo, with first-degree murder, unauthorized use of a vehicle and eluding or attempting to elude a police officer.

The murder charge was issued under Oklahoma’s felony murder rule, which says a suspect may be charged with murder if someone dies while they are committing another felony.

“I just remember falling to the ground at work, and just running out the door,” said Kayla Mestes, Ethan’s older sister, when she heard the news. “I called my sister and let her know that he was gone. I think I was more angry than I was sad because he was just there by himself.”

19 dead

Since May 2016, 19 people have died in 16 OHP chases, according to data compiled by Tulsa World. At least nine of them, including Mestes, weren’t the eluding drivers. All but one of the chases stemmed from stolen property or traffic violations, according to Tulsa World.

In the immediate aftermath of the pursuit, OHP trooper Eric Foster said Carpenter “decided to flee in a felonious manner and put countless lives at risk.”

Foster also said “just looking at the science,” OHP troopers know that pulling off and turning off their lights “doesn’t stop a bad guy from driving recklessly.”

When asked for evidence of this, Foster said OHP has videos of motorists continuing to drive recklessly after law enforcement calls off the chase.

However, StarChase, which manufactures a GPS device that law enforcement agencies use to track fleeing drivers, found in a 2015 federally-funded study that fleeing drivers slow down to normal speeds within two minutes after an officer pulls off.

OHP declined to provide The Transcript with training materials used to justify pursuits and tactical vehicle interventions, citing part of Oklahoma’s Open Records Act that allows the agency to conceal records relating to training, lesson plans and teaching.

Nor did the agency immediately respond to a request for comment or emailed questions about the pursuit and its pursuit policies, or if they use StarChase.

“There are other ways to handle this situation. They should be more pro-life than pro-conviction, or pro-catching-somebody, you know what I mean? If they would have just backed up, I’m pretty sure those kids would have just disappeared into the night, and then they would have popped up during the daytime,” Alires said.

‘I don’t see it as worth the risk’

The StarChase study included 36 cases, and interviews of incarcerated people, and showed that on average, a fleeing suspect tagged with a tracker would slow down to within 10 miles of the posted speed limit in less than two minutes. No fatalities or property damage were reported in the cases used in the study.

The study also showed the suspects in the study were successfully detained later more than 80% of the time.

Seth Stoughton, a University of South Carolina law professor and former police officer who studies policing, said pursuits come with “a significantly elevated risk” that an officer, driver or another person is going to get injured or killed.

He also said tactical vehicle interventions have not been empirically tested well.

“What if (Mills) would have (done a tactical maneuver) on the car, and it would have smacked another car and would have killed a mother or a child, or even another cop?” Alires asked.

Stoughton said he believes police should usually only pursue people suspected of committing violent felonies because pursuits “are inherently dangerous.”

For property crimes, such as a stolen vehicle, he said factors including when the vehicle was stolen should also play into officers’ decision to pursue.

“I’m willing to always acknowledge the extenuating circumstances, but as a general matter, I don’t see it as worth the risk,” he said.

‘Get a law going’

Stoughton also said law enforcement agencies are “all over the place” when it comes to pursuit policies.

This applies to agencies in the Oklahoma City metro area, where Mestes was killed. Oklahoma does not currently have any laws restricting pursuits for law enforcement officers in the state.

In June, the Oklahoma City Police Department changed its pursuit policy so that officers wouldn’t exceed the speed limit by 15 miles per hour on city streets and 25 miles per hour on highways in situations when the officer activates lights and siren.

The policy also orders officers to “self-terminate” pursuits over property crimes, traffic offenses, simple assault and felony eluding in areas including active school zones and active construction zones, where road conditions are poor and when the identity of the suspect is known.

OKCPD updated its policy more than a year after a woman was killed instantly when a fleeing pickup truck collided with her in a chase that reached 95 miles per hour, Oklahoma Watch reported.

In Norman, where Mestes was killed, the police department allows more room for interpretation.

In April, NPD officers chased James Morrison after he, his car and his plates resembled an assault suspect. They chased him at high speeds down State Highway 9, which has one of the highest fatality rates among highways in the state, and tried multiple tactical maneuvers.

The officers eventually shot Morrison after he stepped out of his disabled car and fired a round at them. Detectives later determined Morrison had a possession of firearm after a previous felony conviction and driving under suspension.

When asked if police knew about Morrison’s felony warrant at the time, an NPD spokesperson said Morrison, his car and his plates “matched the description and information available at the time of the incident.

NPD’s policy manual says officers should weigh “safety of the public in the area of the pursuit,” including type of area, and should consider the suspected offense.

While its guidelines for ending a pursuit are not as explicit as OKCPD’s, the department discourages extensive pursuits over suspected misdemeanors, and to take the safety of officers, bystanders and suspects into consideration.

NPD did not immediately respond to emailed questions about their pursuit policies, if they’ve changed them over the years and the outcomes of any changes.

But OHP’s pursuits in particular have had attention at the Capitol. State Rep. Ajay Pittman, D-Oklahoma City, hosted an interim study in September 2021 on the dangers of high-speed chases.

At the study, state public safety director Tim Tipton said OHP has to balance keeping a civil society by catching suspects with the safety of bystanders, troopers and suspects in that order, according to Public Radio Tulsa.

Kayla Mestes said she would like to “get a law going” to define and restrict pursuit practices for police. She believes laws like this could keep deaths like Ethan’s from happening again.

“We’re destroyed. It sucks,” Alires said. “Like I said, he was a good kid. He should have never left. He should have stayed home. But like I said, he had such a big heart.”